For several days in early January, Amsterdam Schiphol Airport stopped behaving like Europe’s most efficient hub and started behaving like a stress test. Persistent snow and ice across Northern Europe tipped operations into a slow-motion failure, with KLM taking the brunt at its home base.

The visible symptoms were brutal. Hundreds of cancellations per day at the peak. Aircraft sitting on taxiways for hours, only to trundle back to the gate. Terminals jammed with stranded passengers. Connections collapsing across the network because Schiphol is not just an airport, it is a keystone.

Behind the scenes, the pressure point was de-icing. KLM ran roughly 25 trucks around the clock and burned through about 85,000 litres of aircraft de-icing fluid per day. Supplies ran so tight that teams were sent into Germany to collect more. This was not a runway problem. It was an airline problem. Aircraft de-icing is the carrier’s responsibility, and sustained winter pushed that system well past its design assumptions.

For passengers, the reality was grimly familiar. Cancelled flights with limited rebooking options, hotel shortages, confusing information, and advice from the airport to leave if your flight was not going. Even when flights operated, reliability evaporated. A hub only works when timing works, and winter tore that apart.

This isn’t a normal January anymore

Yes, January is cold. Snow in the Netherlands is not unprecedented. What made this event different was not intensity, but persistence.

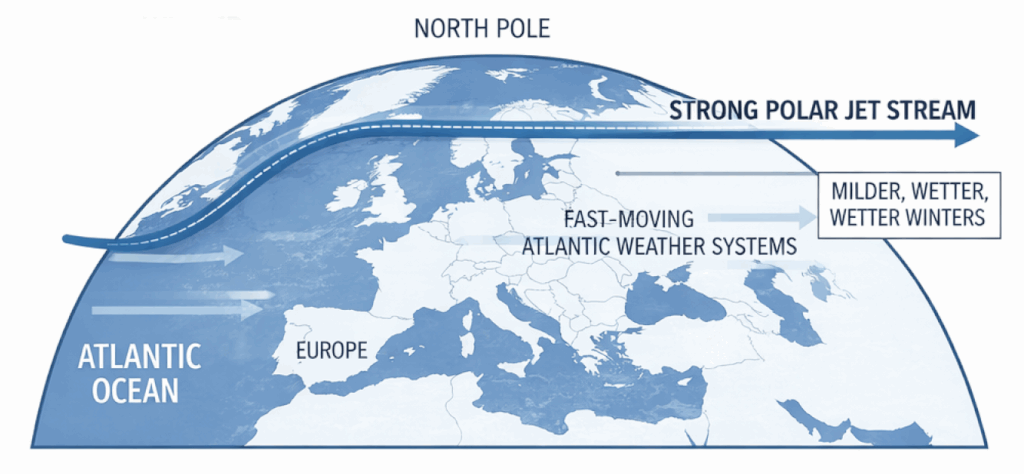

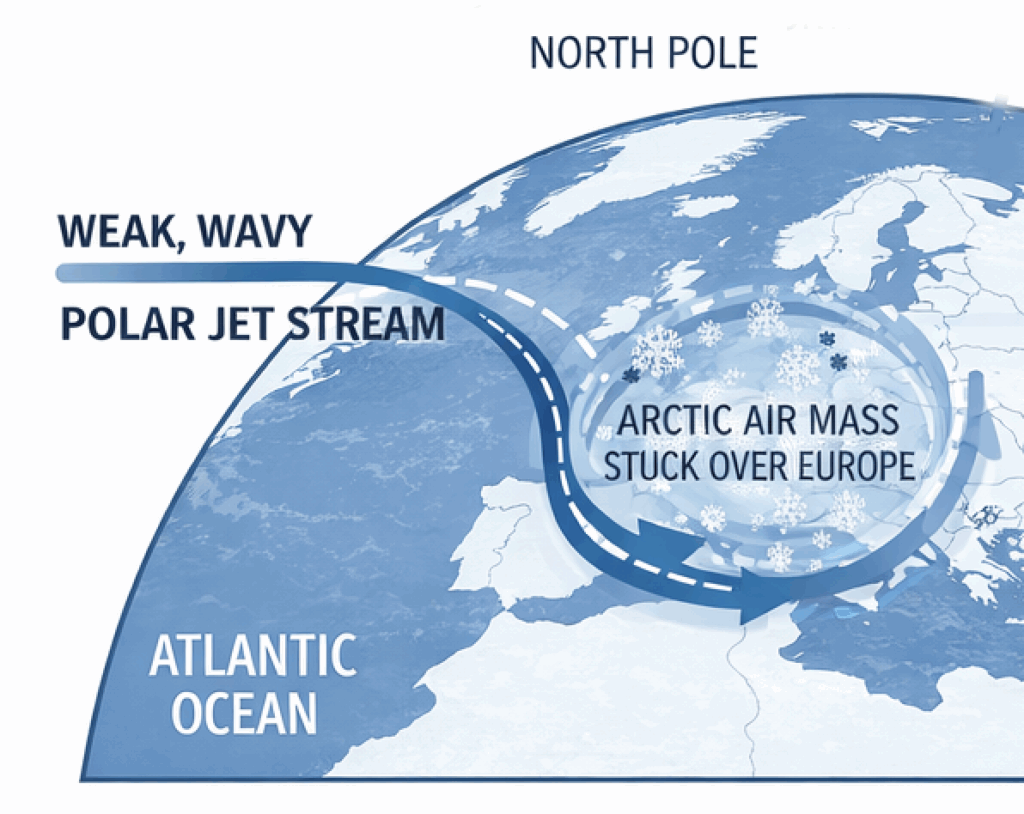

We’re not meteorologists, but very interested to understand what caused this weather event and if it could happen again. The culprit sits far above the airport. The polar jet stream, which normally acts as a fast-moving conveyor belt pushing Atlantic weather systems across Europe, weakened, slowed, and dipped further south than usual. When that happens, Arctic air spills into Northern Europe and then just stays there.

Instead of cold air being flushed out after a day or two, it became the default state. Each snowfall landed on top of the last. Each night reset temperatures back below freezing. De-icing demand stayed permanently high, not spiky.

This is where Arctic warming quietly enters the picture. The Arctic is warming far faster than the rest of the planet. That reduces the temperature contrast between the pole and mid-latitudes, which is what powers a strong, straight jet stream. A weaker contrast means a weaker, wavier jet stream, and that increases the odds of atmospheric blocking and disruption to normal weather patterns in Europe. Colder weather patterns park themselves in place and refuse to move.

The paradox confuses most of us. A warming planet does not mean winters disappear. It means winters become less predictable, with longer, stickier extremes at both ends.

Why Schiphol and its passengers felt it so sharply

Northern Europe’s major hubs are optimised for throughput, not endurance. They are built to handle winter events, not winter states. Staffing, fluid stockpiles, stand layouts, and recovery plans all assume the weather will clear quickly.

When it does not, everything compounds. Missed slots create knock-on delays. Crews time out. Aircraft end up in the wrong places. A hub magnifies small failures into systemic ones.

We’ve seen airports in Canada and the northern USA operate for months each year in conditions that would count as exceptional in Europe. De-icing fluid is stockpiled as standard, winter margins are built into schedules, and taxiway flows, gate usage, and recovery playbooks are designed around the assumption that snow is not going away any time soon.

The compensation claims will come

Because of the circumstances, KLM is likely to be hit with € millions of compensation claims under EU261.

Airlines avoid compensation only if a cancellation or long delay is caused by extraordinary circumstances that:

- Are outside the airline’s control, and

- Could not have been avoided even if all reasonable measures had been taken.

Bad weather can qualify. Operational failure usually does not.

Read Your Flight Was Cancelled: Know Your Rights

Far from a one-off

Our research into this weather event has shown us that what happened at Schiphol, and across other airports in Northern Europe, was not a once-in-a-generation spectacle. It was a preview of more regular winter weather patterns.

As jet stream behaviour becomes more erratic, Northern Europe will see more prolonged winter disruption, even as average temperatures rise. Airports and airlines can either treat these as rare anomalies, or they can accept that resilience now matters as much as efficiency. KLM will be counting the cost of all those avoidable cancelled flights and the compensation passengers will inevitably seek.

Learning from North American cold-weather operations would be a sensible place to start. Bigger buffers. Deeper stockpiles. Winter-first planning rather than winter-as-an-exception. Because the next time the jet stream brings weather disruption to Europe, passengers will not care whether this used to be unusual. They will just point at the airports maintaining good winter operations and demand the same.

Leave a Reply